Charles Dickens

| Charles Dickens | |

|---|---|

Dickens in New York, 1867

|

|

| Born | Charles John Huffam Dickens 7 February 1812 Landport, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 9 June 1870 (aged 58) Higham, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | English |

| Notable work(s) | The Pickwick Papers Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Bleak House Hard Times Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities Great Expectations |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Thomson Hogarth |

| Children | Charles Dickens, Jr. Mary Dickens Kate Perugini Walter Landor Dickens Francis Dickens Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens Henry Fielding Dickens Dora Annie Dickens Edward Dickens |

|

|

|

| Signature |  |

Charles John Huffam Dickens (/ˈtʃɑrlz ˈdɪkɪnz/; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's most memorable fictional characters and is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian period.[1] During his life, his works enjoyed unprecedented fame, and by the twentieth century his literary genius was broadly acknowledged by critics and scholars. His novels and short stories continue to be widely popular.[2][3]

Born in Portsmouth, England, Dickens was forced to leave school to work in a factory when his father was thrown into debtors' prison. Although he had little formal education, his early impoverishment drove him to succeed. Over his career he edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas and hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children's rights, education, and other social reforms.

Dickens sprang to fame with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers. Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire, and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication.[4][5] The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience's reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback.[5] For example, when his wife's chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her disabilities, Dickens went on to improve the character with positive features.[6] His plots were carefully constructed, and Dickens often wove in elements from topical events into his narratives.[7] Masses of the illiterate poor chipped in ha'pennies to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.[8]

Dickens was regarded as the literary colossus of his age.[9] His 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, is one of the most influential works ever written, and it remains popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every artistic genre. Set in London and Paris, his 1859 novel, A Tale of Two Cities, is the best selling novel of all time.[10] His creative genius has been praised by fellow writers—from Leo Tolstoy to George Orwell and G. K. Chesterton—for its realism, comedy, prose style, unique characterisations, and social criticism. On the other hand Oscar Wilde, Henry James and Virginia Woolf complained of a lack of psychological depth, loose writing, and a vein of saccharine sentimentalism. The term Dickensian is used to describe something that is reminiscent of Dickens and his writings, such as poor social conditions or comically repulsive characters.[11]

Contents

Life

Early years

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born on 7 February 1812, at Landport in Portsea Island, the second of eight children to John Dickens (1785–1851) and Elizabeth Dickens (née Barrow; 1789–1863). His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay Office and was temporarily on duty in the district. Very soon after his birth the family moved to Norfolk Street, Bloomsbury, and then, when he was four, to Chatham, Kent, where he spent his formative years until the age of 11. His early years seem to have been idyllic, though he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".[12]

Charles spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. He retained poignant memories of childhood, helped by a near-photographic memory of people and events, which he used in his writing.[13] His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office gave him a few years of private education, first at a dame-school, and then at a school run by William Giles, a dissenter, in Chatham.[14]

Illustration by Fred Bernard of Dickens at work in a shoe-blacking factory after his father had been sent to the Marshalsea, published in the 1892 edition of Forster's Life of Dickens[15]

This period came to an abrupt end when financial difficulties forced the family to move to Camden Town in London in 1822. Living beyond his means,[16] John Dickens was forced by his creditors into the Marshalsea debtors' prison in Southwark London in 1824. His wife and youngest children joined him there, as was the practice at the time. Charles, then 12 years old, boarded with Elizabeth Roylance, a family friend, at 112 College Place, Camden Town.[17] Roylance was "a reduced [impoverished] old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in Dombey and Son. Later, he lived in a back-attic in the house of an agent for the Insolvent Court, Archibald Russell, "a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman ... with a quiet old wife" and lame son, in Lant Street in The Borough.[18] They provided the inspiration for the Garlands in The Old Curiosity Shop.[19]

On Sundays—with his sister Frances, free from her studies at the Royal Academy of Music—he spent the day at the Marshalsea.[20] Dickens would later use the prison as a setting in Little Dorrit. To pay for his board and to help his family, Dickens was forced to leave school and work ten-hour days at Warren's Blacking Warehouse, on Hungerford Stairs, near the present Charing Cross railway station, where he earned six shillings a week pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. The strenuous and often harsh working conditions made a lasting impression on Dickens and later influenced his fiction and essays, becoming the foundation of his interest in the reform of socio-economic and labour conditions, the rigours of which he believed were unfairly borne by the poor. He later wrote that he wondered "how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age".[21] As he recalled to John Forster (from The Life of Charles Dickens):

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.[21]

A few months after his imprisonment, John Dickens's paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him the sum of £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was granted release from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors, and he and his family left Marshalsea,[22] for the home of Mrs. Roylance.

Charles' mother Elizabeth Dickens did not immediately remove him from the boot-blacking factory. This incident may have done much to confirm Dickens's view that a father should rule the family, a mother find her proper sphere inside the home. "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back". His mother's failure to request his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.[23]

Righteous anger stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, David Copperfield:[24] "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!"[25]

Charles was eventually sent to the Wellington House Academy in Camden Town, but did not consider it to be a good school. "Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr. Creakle's Establishment in David Copperfield."[25]

Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray's Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828. Then, having learned Gurney's system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors' Commons, and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years.[26][27] This education was to inform works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House—whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public and served as a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law".

In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.[28]

Journalism and early novels

In 1832, at age 20, Dickens was energetic, full of good humour, enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, lacked a clear sense of what he wanted to become, and yet knew he wanted to be famous. He was drawn to the theatre and landed an acting audition at Covent Garden, for which he prepared meticulously but which he missed because of a cold, ending his aspirations for a career on the stage. A year later he submitted his first story, "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" to the London periodical, Monthly Magazine.[29] He rented rooms at Furnival's Inn and worked as a political journalist, reporting on Parliamentary debate and travelling across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz—Boz being a family nickname he employed as a pseudonym for some years—published in 1836.[30][31] Dickens apparently adopted it from the nickname Moses, which he had given to his youngest brother Augustus Dickens, after a character in Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. When pronounced by anyone with a head cold, 'Moses' became 'Boses', and was later shortened to Boz.[31][32] Dickens's own name was considered "queer" by a contemporary critic, who wrote in 1849: "Mr Dickens, as if in revenge for his own queer name, does bestow still queerer ones upon his fictitious creations." He continued to contribute to and edit journals throughout his literary career.[29]

The success of these sketches led to a proposal from publishers Chapman and Hall for Dickens to supply text to match Robert Seymour's engraved illustrations in a monthly letterpress. Seymour committed suicide after the second instalment and Dickens, who wanted to write a connected series of sketches, hired "Phiz" to provide the engravings (which were reduced from four to two per instalment) for the story. The resulting story was The Pickwick Papers with the final instalment selling 40,000 copies.[29]

In November 1836 Dickens accepted the job of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, a position he held for three years, until he fell out with the owner.[33] In 1836 as he finished the last instalments of The Pickwick Papers he began writing the beginning instalments of Oliver Twist—writing as many as 90 pages a month—while continuing work on Bentley's, and also writing four plays, the production of which he oversaw. Oliver Twist, published in 1838, became one of Dickens's better known stories, with dialogue that transferred well to the stage (most likely because he was writing stage plays at the same time) and, more importantly, it was the first Victorian novel with a child protagonist.[34]

On 2 April 1836, after a one year engagement during which he wrote The Pickwick Papers, he married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1816–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle.[35] After a brief honeymoon in Chalk, Kent, they returned to lodgings at Furnival's Inn.[36] The first of ten children, Charley, was born in January 1837, and a few months later the family set up home in Bloomsbury at 48 Doughty Street, London, (on which Charles had a three-year lease at £80 a year) from 25 March 1837 until December 1839.[35][37] Dickens's younger brother Frederick and Catherine's 17-year-old sister Mary moved in with them. Dickens became very attached to Mary, and she died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837. Dickens idealised her and is thought to have drawn on memories of her for his later descriptions of Rose Maylie, Little Nell and Florence Dombey.[38] His grief was so great that he was unable to make the deadline for the June instalment of Pickwick Papers and had to cancel the Oliver Twist instalment that month as well.[34]

At the same time, his success as a novelist continued. The young Queen Victoria read both Oliver Twist and Pickwick, staying up until midnight to discuss them.[39]Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39), The Old Curiosity Shop and, finally, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty as part of the Master Humphrey's Clock series (1840–41), were all published in monthly instalments before being made into books.[40]

First visit to the United States

In 1842, Dickens and his wife made their first trip to the United States and Canada. At this time Georgina Hogarth, another sister of Catherine, joined the Dickens household, now living at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, to care for the young family they had left behind.[41] She remained with them as housekeeper, organiser, adviser and friend until Dickens's death in 1870.[42]

He described his impressions in a travelogue, American Notes for General Circulation. Some of the episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–44) also drew on these first-hand experiences. Dickens includes in Notes a powerful condemnation of slavery, which he had attacked as early as The Pickwick Papers, correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad.[43] During his visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures and raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America.[44][45] He persuaded twenty five writers, headed by Washington Irving, to sign a petition for him to take to Congress, but the press were generally hostile to this, saying that he should be grateful for his popularity and that it was mercenary to complain about his work being pirated.[46]

Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, A Christmas Carol, written in 1843, which was followed by The Chimes in 1844 and The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845. Of these A Christmas Carol was most popular and, tapping into an old tradition, did much to promote a renewed enthusiasm for the joys of Christmas in Britain and America.[47] The seeds for the story were planted in Dickens's mind during a trip to Manchester to witness the conditions of the manufacturing workers there. This, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School, caused Dickens to resolve to "strike a sledge hammer blow" for the poor. As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he "wept and laughed, and wept again" as he "walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed."[48]

After living briefly in Italy (1844), Dickens travelled to Switzerland (1846); it was here he began work on Dombey and Son (1846–48). This and David Copperfield (1849–50) mark a significant artistic break in Dickens's career as his novels became more serious in theme and more carefully planned than his early works.

Philanthropy

In May 1846 Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women of the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named "Urania Cottage", in the Lime Grove section of Shepherds Bush, which he was to manage for ten years,[49] setting the house rules and reviewing the accounts and interviewing prospective residents.[50] Emigration and marriage were central to Dickens's agenda for the women on leaving Urania Cottage, from which it is estimated that about 100 women graduated between 1847 and 1859.[51]

Religious views

Dickens was a professing Christian,[52] who would be described by his son Henry Fielding Dickens as someone who "possessed deep religious convictions". Though in the early 1840s Dickens had showed an interest in Unitarian Christianity, he never strayed from his attachment to popular lay Anglicanism.[53] He would also write a religious work called The Life of Our Lord (1849), which was a short book about the life of Jesus Christ, and was written with the purpose of inculcating his faith to his children and family.[54][55]

On the other hand, he disapproved of denominations such as Roman Catholicism and the 19th centhury evangelicalism and addressed critically what he saw as the hypocrisy of religious institutions and philosophies like spiritualism, all of which he considered deviations from the true spirit of Christianity.[56]

Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky would refer to Dickens as "that great Christian writer".[57][58]

Middle years

In late November 1851, Dickens moved into Tavistock House where he wrote Bleak House (1852–53), Hard Times (1854) and Little Dorrit (1856).[59] It was here that he indulged in the amateur theatricals which are described in Forster's "Life".[60] During this period he worked closely with the novelist and playwright Wilkie Collins. In 1856, his income from writing allowed him to buy Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent. As a child, Dickens had walked past the house and dreamed of living in it. The area was also the scene of some of the events of Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, and this literary connection pleased him.[61]

In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play The Frozen Deep, which he and his protégé Wilkie Collins had written. Dickens fell deeply in love with one of the actresses, Ellen Ternan, and this passion was to last the rest of his life.[62] Dickens was 45 and Ternan 18 when he made the decision, which went strongly against Victorian convention, to separate from his wife, Catherine, in 1858—divorce was still unthinkable for someone as famous as he was. When Catherine left, never to see her husband again, she took with her one child, leaving the other children to be raised by her sister Georgina who chose to stay at Gad's Hill.[42]

During this period, whilst pondering a project to give public readings for his own profit, Dickens was approached by Great Ormond Street Hospital to help it survive its first major financial crisis through a charitable appeal. His 'Drooping Buds' essay in Household Words earlier in 3 April 1852 was considered by the hospital's founders to have been the catalyst for the hospital's success.[63] Dickens, whose philanthropy was well-known, was asked by his friend, the hospital's founder Charles West, to preside over the appeal, and he threw himself into the task, heart and soul.[64] Dickens's public readings secured sufficient funds for an endowment to put the hospital on a sound financial footing —one reading on 9 February 1858 alone raised £3,000.[65][66][67]

After separating from Catherine,[68] Dickens undertook a series of hugely popular and remunerative reading tours which, together with his journalism, were to absorb most of his creative energies for the next decade, in which he was to write only two more novels.[69] His first reading tour, lasting from April 1858 to February 1859, consisted of 129 appearances in 49 different towns throughout England, Scotland and Ireland.[70] Dickens's continued fascination with the theatrical world was written into the theatre scenes in Nicholas Nickleby, but more importantly he found an outlet in public readings. In 1866, he undertook a series of public readings in England and Scotland, with more the following year in England and Ireland.

Major works, A Tale of Two Cities (1859) and Great Expectations (1861), soon followed, and were resounding successes. During this time he was also the publisher and editor of, and a major contributor to, the journals Household Words (1850–1859) and All the Year Round (1858–1870).[71]

In early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill, Dickens made a great bonfire of almost his entire correspondence—only those letters on business matters were spared. Since Ellen Ternan also destroyed all of his letters to her,[72] the extent of the affair between the two remains speculative.[73] In the 1930s, Thomas Wright recounted that Ternan had unburdened herself with a Canon Benham, and gave currency to rumours they had been lovers.[74] That the two had a son who died in infancy was alleged by Dickens's daughter, Kate Perugini, whom Gladys Storey had interviewed before her death in 1929. Storey published her account in Dickens and Daughter,[75][76] but no contemporary evidence exists. On his death, Dickens settled an annuity on Ternan which made her a financially independent woman. Claire Tomalin's book, The Invisible Woman, argues that Ternan lived with Dickens secretly for the last 13 years of his life. The book was subsequently turned into a play, Little Nell, by Simon Gray, and a 2013 film.

In the same period, Dickens furthered his interest in the paranormal, becoming one of the early members of The Ghost Club.[77]

In June 1862 he was offered £10,000 for a reading tour of Australia.[78] He was enthusiastic, and even planned a travel book, The Uncommercial Traveller Upside Down, but ultimately decided against the tour.[79] However, two of his sons—Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens and Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens—migrated to Australia, Edward becoming a member of the Parliament of New South Wales as Member for Wilcannia 1889–94.[80][81]

Last years

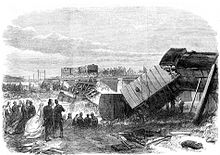

On 9 June 1865, while returning from Paris with Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash. The first seven carriages of the train plunged off a cast iron bridge that was under repair. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was travelling. Before rescuers arrived, Dickens tended and comforted the wounded and the dying with a flask of brandy and a hat refreshed with water, and saved some lives. Before leaving, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it.[82] Dickens later used this experience as material for his short ghost story, "The Signal-Man", in which the central character has a premonition of his own death in a rail crash. He also based the story on several previous rail accidents, such as the Clayton Tunnel rail crash of 1861.

Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquest to avoid disclosing that he had been travelling with Ternan and her mother, which would have caused a scandal. Although physically unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the trauma of the Staplehurst crash, and his normally prolific writing shrank to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Second visit to the United States

On 9 November 1867, Dickens sailed from Liverpool for his second American reading tour. Landing at Boston, he devoted the rest of the month to a round of dinners with such notables as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his American publisher James Thomas Fields. In early December, the readings began—he was to perform 76 readings, netting £19,000, from December 1867 to April 1868[83]—and Dickens spent the month shuttling between Boston and New York, where alone he gave 22 readings at Steinway Hall for this period. Although he had started to suffer from what he called the "true American catarrh", he kept to a schedule that would have challenged a much younger man, even managing to squeeze in some sleighing in Central Park.

Poster promoting a reading by Dickens in Nottingham dated 4 February 1869, two months before he suffered a mild stroke.

During his travels, he saw a significant change in the people and the circumstances of America. His final appearance was at a banquet the American Press held in his honour at Delmonico's on 18 April, when he promised never to denounce America again. By the end of the tour, the author could hardly manage solid food, subsisting on champagne and eggs beaten in sherry. On 23 April, he boarded his ship to return to Britain, barely escaping a Federal Tax Lien against the proceeds of his lecture tour.[84]

Farewell readings

Between 1868 and 1869, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland, and Ireland, beginning on 6 October. He managed, of a contracted 100 readings, to deliver 75 in the provinces, with a further 12 in London.[83] As he pressed on he was affected by giddiness and fits of paralysis and collapsed on 22 April 1869, at Preston in Lancashire, and on doctor's advice, the tour was cancelled.[85] After further provincial readings were cancelled, he began work on his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. It was fashionable in the 1860s to 'do the slums' and, in company, Dickens visited opium dens in Shadwell, where he witnessed an elderly addict known as "Laskar Sal", who formed the model for the "Opium Sal" subsequently featured in his mystery novel, Edwin Drood.[86]

When he had regained sufficient strength, Dickens arranged, with medical approval, for a final series of readings at least partially to make up to his sponsors what they had lost due to his illness. There were to be 12 performances, running between 11 January and 15 March 1870, the last taking place at 8:00 pm at St. James's Hall in London. Although in grave health by this time, he read A Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick. On 2 May, he made his last public appearance at a Royal Academy Banquet in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, paying a special tribute on the death of his friend, illustrator Daniel Maclise.[87]

Death

Samuel Luke Fildes—The Empty Chair. Fildes was illustrating "Edwin Drood" at the time of Charles Dickens' death. The engraving shows Dickens's empty chair in his study at Gads Hill Place. It appeared in the Christmas 1870 edition of the The Graphic and thousands of prints of it were sold.[88]

On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered another stroke at his home after a full day's work on Edwin Drood. He never regained consciousness, and the next day, on 9 June, five years to the day after the Staplehurst rail crash, he died at Gad's Hill Place. Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral "in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner,"[89] he was laid to rest in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey. A printed epitaph circulated at the time of the funeral reads: "To the Memory of Charles Dickens (England's most popular author) who died at his residence, Higham, near Rochester, Kent, 9 June 1870, aged 58 years. He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world."[90] His last words were: "On the ground", in response to his sister-in-law Georgina's request that he lie down.[91][nb 1]

On Sunday, 19 June 1870, five days after Dickens was buried in the Abbey, Dean Arthur Penrhyn Stanley delivered a memorial elegy, lauding "the genial and loving humorist whom we now mourn", for showing by his own example "that even in dealing with the darkest scenes and the most degraded characters, genius could still be clean, and mirth could be innocent." Pointing to the fresh flowers that adorned the novelist's grave, Stanley assured those present that "the spot would thenceforth be a sacred one with both the New World and the Old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue."[92]

In his Will, that he had drafted just over a year prior to his death, Dickens left the care of his £80,000 estate to his longtime colleague John Forster (biographer) and his "best and truest friend" Georgina Hogarth who, along with Dickens' two sons, also received a tax-free sum of £8,000 (about £800,000 in present terms). Although Dickens and his wife had been separated for a number of years at the time of his death, he had provided her with an annual income of £600 and made her similar allowances in his Will. He also bequeathed the sum of £19 19s to each of the servants in his employment at the time of his demise.[93]

Literary style

Dickens loved the style of the 18th century picaresque novels which he found in abundance on his father's shelves. According to Ackroyd, other than these, perhaps the most important literary influence on him was derived from the fables of The Arabian Nights.[94]

Dickens' Dream by Robert William Buss, portraying Dickens at his desk at Gads Hill Place surrounded by many of his characters

His writing style is marked by a profuse linguistic creativity.[95] Satire, flourishing in his gift for caricature, is his forte. An early reviewer compared him to Hogarth for his keen practical sense of the ludicrous side of life, though his acclaimed mastery of varieties of class idiom may in fact mirror the conventions of contemporary popular theatre.[96] Dickens worked intensively on developing arresting names for his characters that would reverberate with associations for his readers, and assist the development of motifs in the storyline, giving what one critic calls an "allegorical impetus" to the novels' meanings.[95] To cite one of numerous examples, the name Mr. Murdstone in David Copperfield conjures up twin allusions to "murder" and stony coldness.[97] His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery—he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator"—are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats, or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy.

The author worked closely with his illustrators, supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them. He would brief the illustrator on plans for each month's instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them. Marcus Stone, illustrator of Our Mutual Friend, recalled that the author was always "ready to describe down to the minutest details the personal characteristics, and ... life-history of the creations of his fancy."[98]

Characters

Dickens's biographer Claire Tomalin regards him as the greatest creator of character in English fiction after Shakespeare.[99] Dickensian characters, are amongst the most memorable in English literature, especially so because of their typically whimsical names. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Jacob Marley, Bob Cratchit, Oliver Twist, The Artful Dodger, Fagin, Bill Sikes, Pip, Miss Havisham, Sydney Carton, Charles Darnay, David Copperfield, Mr. Micawber, Abel Magwitch, Daniel Quilp, Samuel Pickwick, Wackford Squeers, and Uriah Heep are so well known as to be part and parcel of British culture, and in some cases have passed into ordinary language: a scrooge, for example, is a miser.

His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. "Gamp" became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs Gamp, and "Pickwickian", "Pecksniffian", and "Gradgrind" all entered dictionaries due to Dickens's original portraits of such characters who were, respectively, quixotic, hypocritical, and vapidly factual. Many were drawn from real life: Mrs Nickleby is based on his mother, though she didn't recognise herself in the portrait,[100] just as Mr Micawber is constructed from aspects of his father's 'rhetorical exuberance':[101] Harold Skimpole in Bleak House is based on James Henry Leigh Hunt: his wife's dwarfish chiropodist recognised herself in Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield.[102][103] Perhaps Dickens's impressions on his meeting with Hans Christian Andersen informed the delineation of Uriah Heep.[104]

Virginia Woolf maintained that "we remodel our psychological geography when we read Dickens" as he produces "characters who exist not in detail, not accurately or exactly, but abundantly in a cluster of wild yet extraordinarily revealing remarks."[105]

One "character" vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames, all aspects of the capital are described over the course of his body of work.

Autobiographical elements

An original illustration by Phiz from the novel "David Copperfield", widely regarded as Dickens's most autobiographical work.

Authors frequently draw their portraits of characters from people they have known in real life. David Copperfield is regarded as strongly autobiographical. The scenes of interminable court cases and legal arguments in Bleak House reflect Dickens's experiences as a law clerk and court reporter, and in particular his direct experience of the law's procedural delay during 1844 when he sued publishers in Chancery for breach of copyright.[106] Dickens's father was sent to prison for debt, and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in Little Dorrit resulting from Dickens's own experiences of the institution.[107] Lucy Stroughill, a childhood sweetheart, may have affected several of Dickens's portraits of girls such as Little Em'ly in David Copperfield and Lucie Manette in A Tale of Two Cities.[108][nb 2] Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death, when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated. Though Skimpole brutally sends up Leigh Hunt, some critics have detected in his portrait features of Dickens's own character, which he sought to exorcise by self-parody.[109]

Episodic writing

Most of Dickens's major novels were first written in monthly or weekly instalments in journals such as Master Humphrey's Clock and Household Words, later reprinted in book form. These instalments made the stories cheap, accessible and the series of regular cliff-hangers made each new episode widely anticipated. When The Old Curiosity Shop was being serialised, American fans even waited at the docks in New York, shouting out to the crew of an incoming ship, "Is little Nell dead?"[110] Part of Dickens's great talent was to incorporate this episodic writing style but still end up with a coherent novel at the end.

Another important impact of Dickens's episodic writing style resulted from his exposure to the opinions of his readers and friends. His friend Forster had a significant hand in reviewing his drafts, an influence that went beyond matters of punctuation. He toned down melodramatic and sensationalist exaggerations, cut long passages (such as the episode of Quilp's drowning in The Old Curiosity Shop), and made suggestions about plot and character. It was he who suggested that Charley Bates should be redeemed in Oliver Twist. Dickens had not thought of killing Little Nell, and it was Forster who advised him to entertain this possibility as necessary to his conception of the heroine.[111]

Dicken's serialisation of his novels was not uncriticised by other authors. In Robert Louis Stevenson's novel "The Wrecker", there is a comment by Captain Nares, investigating an abandoned ship: "See! They were writing up the log," said Nares, pointing to the ink-bottle. "Caught napping, as usual. I wonder if there ever was a captain yet that lost a ship with his log-book up to date? He generally has about a month to fill up on a clean break, like Charles Dickens and his serial novels."

Social commentary

Dickens's novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. He was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society. In a New York address, he expressed his belief that "Virtue shows quite as well in rags and patches as she does in purple and fine linen".[112] Dickens's second novel, Oliver Twist (1839), shocked readers with its images of poverty and crime: it destroyed middle class polemics about criminals, making impossible any pretence to ignorance about what poverty entailed.[113][114]

Literary techniques

Dickens is often described as using 'idealised' characters and highly sentimental scenes to contrast with his caricatures and the ugly social truths he reveals. The story of Nell Trent in The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) was received as extraordinarily moving by contemporary readers but viewed as ludicrously sentimental by Oscar Wilde. "You would need to have a heart of stone", he declared in one of his famous witticisms, "not to laugh at the death of little Nell."[115]G. K. Chesterton, stating that "It is not the death of little Nell, but the life of little Nell, that I object to", argued that the maudlin effect of his description of her life owed much to the gregarious nature of Dickens's grief, his 'despotic' use of people's feelings to move them to tears in works like this.[116]

The question as to whether Charles Dickens belongs to the tradition of the sentimental novel is debatable. Valerie Purton, in her recent Dickens and the Sentimental Tradition, sees him continuing aspects of this tradition, and argues that his "sentimental scenes and characters [are] as crucial to the overall power of the novels as his darker or comic figures and scenes", and that "Dombey and Son is [ ... ] Dickens's greatest triumph in the sentimentalist tradition".[117] However, the Encyclopædia Britannica online comments that, despite "patches of emotional excess", such as the reported death of Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol (1843), "Dickens cannot really be termed a sentimental novelist".[118]

In Oliver Twist Dickens provides readers with an idealised portrait of a boy so inherently and unrealistically "good" that his values are never subverted by either brutal orphanages or coerced involvement in a gang of young pickpockets. While later novels also centre on idealised characters (Esther Summerson in Bleak House and Amy Dorrit in Little Dorrit), this idealism serves only to highlight Dickens's goal of poignant social commentary. Many of his novels are concerned with social realism, focusing on mechanisms of social control that direct people's lives (for instance, factory networks in Hard Times and hypocritical exclusionary class codes in Our Mutual Friend).[citation needed] Dickens's fiction, reflecting what he believed to be true of his own life, makes frequent use of coincidence, either for comic effect or to emphasise the idea of providence.[119] Oliver Twist turns out to be the lost nephew of the upper-class family that randomly rescues him from the dangers of the pickpocket group. Such coincidences are a staple of 18th-century picaresque novels, such as Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, which Dickens enjoyed reading as a youth.[120]

Reception

Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time,[121] and remains one of the best known and most read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print,[122] and have been adapted continually for the screen since the invention of cinema,[123] with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens's works documented.[124] Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime, and as early as 1913, a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made.

Among fellow writers, Dickens has been both lionised and mocked. Leo Tolstoy, G. K. Chesterton and George Orwell praised his realism, comic voice, prose fluency, and genius for satiric caricature, as well as his passionate advocacy on behalf of children and the poor. On the other hand, Oscar Wilde generally disparaged his depiction of character, while admiring his gift for caricature;[125] His late contemporary William Wordsworth, by then Poet laureate, thought him a "very talkative, vulgar young person", adding he had not read a line of his work; Dickens in return thought Wordsworth "a dreadful Old Ass".[126] Henry James denied him a premier position, calling him "the greatest of superficial novelists": Dickens failed to endow his characters with psychological depth and the novels, "loose baggy monsters",[127] betrayed a "cavalier organisation".[128] Virginia Woolf had a love-hate relationship with his works, finding his novels "mesmerizing" while reproving him for his sentimentalism and a commonplace style.[129]

It is likely that A Christmas Carol stands as his best-known story, with frequent new adaptations. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, with many versions dating from the early years of cinema.[130] According to the historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of the observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by A Christmas Carol. Dickens catalysed the emerging Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the dwindling community-based and church-centred observations, as new middle-class expectations arose.[131] Its archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) entered into Western cultural consciousness. A prominent phrase from the tale, 'Merry Christmas', was popularised following the appearance of the story.[132] The term Scrooge became a synonym for miser, and his dismissive put-down exclamation 'Bah! Humbug!' likewise gained currency as an idiom.[133] Novelist William Makepeace Thackeray called the book "a national benefit, and to every man and woman who reads it a personal kindness".[130]

At a time when Britain was the major economic and political power of the world, Dickens highlighted the life of the forgotten poor and disadvantaged within society. Through his journalism he campaigned on specific issues—such as sanitation and the workhouse—but his fiction probably demonstrated its greatest prowess in changing public opinion in regard to class inequalities. He often depicted the exploitation and oppression of the poor and condemned the public officials and institutions that not only allowed such abuses to exist, but flourished as a result. His most strident indictment of this condition is in Hard Times (1854), Dickens's only novel-length treatment of the industrial working class. In this work, he uses both vitriol and satire to illustrate how this marginalised social stratum was termed "Hands" by the factory owners; that is, not really "people" but rather only appendages of the machines they operated. His writings inspired others, in particular journalists and political figures, to address such problems of class oppression. For example, the prison scenes in The Pickwick Papers are claimed to have been influential in having the Fleet Prison shut down. Karl Marx asserted that Dickens ..."issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together".[134]George Bernard Shaw even remarked that Great Expectations was more seditious than Marx's own Das Kapital.[134] The exceptional popularity of Dickens's novels, even those with socially oppositional themes (Bleak House, 1853; Little Dorrit, 1857; Our Mutual Friend, 1865), not only underscored his almost preternatural ability to create compelling storylines and unforgettable characters, but also ensured that the Victorian public confronted issues of social justice that had commonly been ignored. It has been argued that his technique of flooding his narratives with an 'unruly superfluity of material' that, in the gradual dénouement, yields up an unsuspected order, influenced the organisation of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species.[135]

His fiction, with often vivid descriptions of life in 19th-century England, has inaccurately and anachronistically come to symbolise on a global level Victorian society (1837–1901) as uniformly "Dickensian", when in fact, his novels' time scope spanned from the 1770s to the 1860s. In the decade following his death in 1870, a more intense degree of socially and philosophically pessimistic perspectives invested British fiction; such themes stood in marked contrast to the religious faith that ultimately held together even the bleakest of Dickens's novels. Dickens clearly influenced later Victorian novelists such as Thomas Hardy and George Gissing; their works display a greater willingness to confront and challenge the Victorian institution of religion. They also portray characters caught up by social forces (primarily via lower-class conditions), but they usually steered them to tragic ends beyond their control.

Influence and legacy

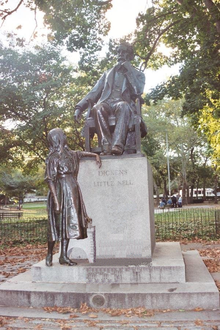

Museums and festivals celebrating Dickens's life and works exist in many places with which Dickens was associated, such as the Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth, the house in which he was born. The original manuscripts of many of his novels, as well as printers' proofs, first editions, and illustrations from the collection of Dickens's friend John Forster are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum.[136] Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected in his honour. A life-size bronze statue of Dickens, cast in 1891 by Francis Edwin Elwell, stands in Clark Park in the Spruce Hill neighbourhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Another life-size statue of Dickens is located at Centennial Park, Sydney, Australia.[137] In 2014, a life-size statue was unveiled near his birthplace in Portsmouth on the 202nd anniversary of his birth; this was supported by the author's great-great grandsons, Ian and Gerald Dickens.[138][139]

Dickens was commemorated on the Series E £10 note issued by the Bank of England that was in circulation in the UK between 1992 and 2003. His portrait appeared on the reverse of the note accompanied by a scene from The Pickwick Papers. The Charles Dickens School is a high school in Broadstairs, Kent, that is named after him. A theme park, Dickens World, standing in part on the site of the former naval dockyard where Dickens's father once worked in the Navy Pay Office, opened in Chatham in 2007. To celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens in 2012, the Museum of London held the UK's first major exhibition on the author in 40 years.[140] In 2002, Dickens was placed at number 41 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[141] American literary critic Harold Bloom placed Dickens among the greatest Western Writers of all time.[142] In the UK survey entitled The Big Read carried out by the BBC in 2003, five of Dickens's books were named in the Top 100.[143]

Notable works

Charles Dickens published over a dozen major novels, a large number of short stories (including a number of Christmas-themed stories), a handful of plays, and several non-fiction books. Dickens's novels were initially serialised in weekly and monthly magazines, then reprinted in standard book formats.

Novels

|

|

Short story collections

- Sketches by Boz (1836)

- The Mudfog Papers (1837) in Bentley's Miscellany magazine

- Reprinted Pieces (1861)

- The Uncommercial Traveller (1860–1869)

|

Christmas numbers of Household Words magazine:

|

Christmas numbers of All the Year Round magazine:

|

Selected non-fiction, poetry, and plays

|

|

Taken from Wikipedia

Poems by this Poet

|

Poem |

Post date | Rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Child's Hymn | 30 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

1 |

| A fine Old English Gentleman | 30 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |

| Fine Old English Gentleman, The; New Version | 29 November 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |

| Gabriel's Grub Song | 31 July 2013 |

(2 votes) |

0 |

| George Edmunds' Song | 31 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |

| Little Nell's Funeral | 31 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |

| Lucy's Song | 31 July 2013 |

(3 votes) |

0 |

| Squire Norton's Song | 31 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |

| The Cannibals' Grace before Meat | 19 May 2014 |

No votes yet |

0 |

| The Hymn Of The Wiltshire Laborers | 31 July 2013 |

(1 vote) |

0 |